From the Archives: Incarceration of Japanese Americans During WWII

By Diane Hall, Eta Upsilon-Drexel, archivist/historian, and Louis Green, assistant director of belonging efforts

Content Warning: This blog post contains historically accurate information regarding xenophobia and racism directed at people of Japanese ancestry in the United States during WWII. Information on correct terminology around this topic is provided, with additional content and resource lists for further exploration.

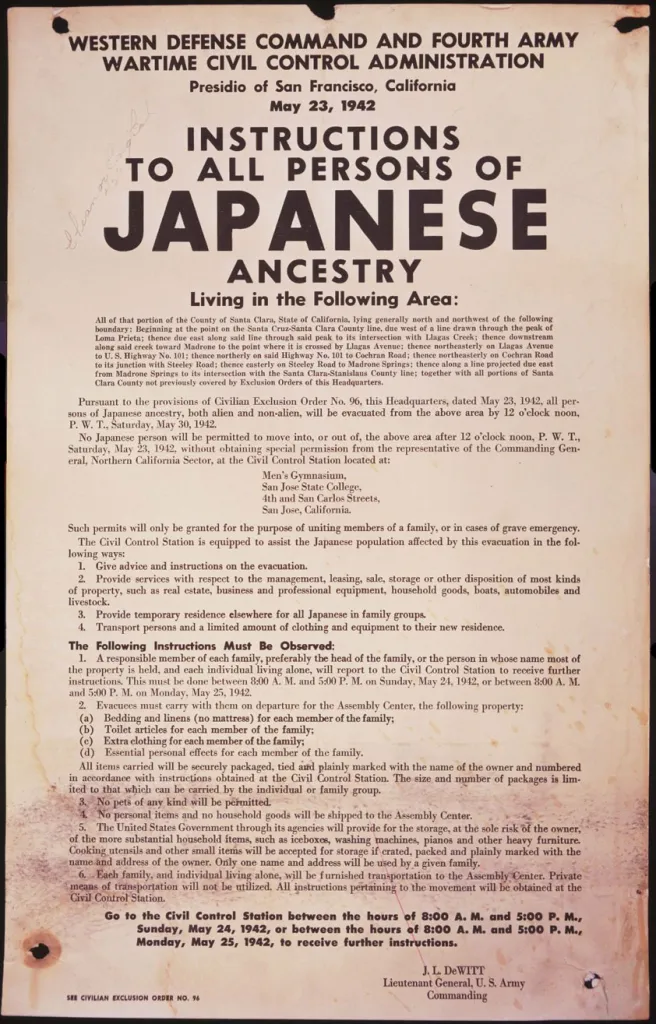

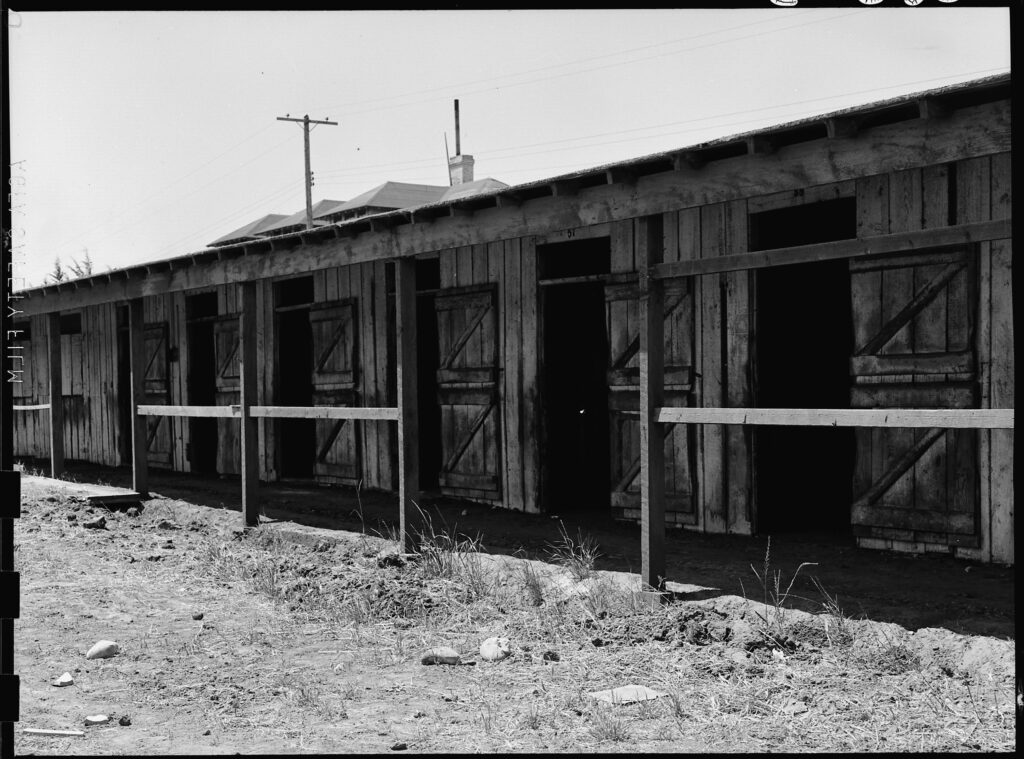

It might sound like the plot of a dystopian novel, but the government did indeed incarcerate its own citizens during World War II, not because they were convicted of any crime, but simply because of their Japanese ancestry. These individuals were ordered to "Assembly Centers" with as little as a one-weeki notice, often resulting in the loss of homes, businesses and other assets. The assembly centers, often repurposed structures like horse stables, housed people before they were transported to remote camps surrounded by 24-hour guards. Shockingly, no one was exempt from this ordeal – the elderly, those with disabilities, young children and pregnant individuals all found themselves forcibly relocated.ii

This grim reality affected 120,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry in the United States during World War II. Among them, approximately 80,000 were nisei (second generation) and sansei (third generation), while the remaining 40,000 were issei (first generation).iii Despite having lived in the United States for decades, issei were not eligible for citizenship at the time.iv

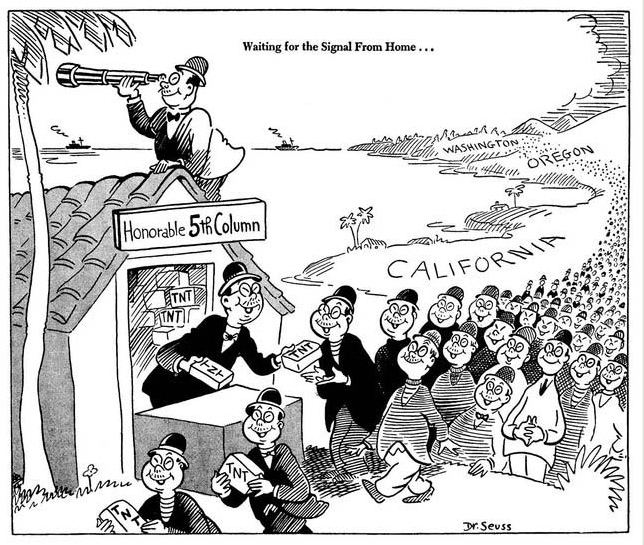

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force intensified discrimination and hostility towards Japanese Americans. Paranoia swept the country, fueled by fears of a Japanese "Fifth Column." On February 19, 1942, just ten weeks after the bombing, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. While not explicitly singling out those of Japanese heritage, this order effectively stripped them of all civil rights, leading to their forced removal from homes into hastily built camps surrounded by armed guards.v

The effects of Executive Order 9066 and the resulting forcible removal of Japanese Americans from their homes and communities were profound and long-lasting. The loss of property devastated the financial security of many of the incarcerated individuals and families. It is estimated that Japanese Americans lost $400 million because of their forced relocation.vi Later research also found many suffered long-term negative physical and psychological problems because of this ordeal.vii

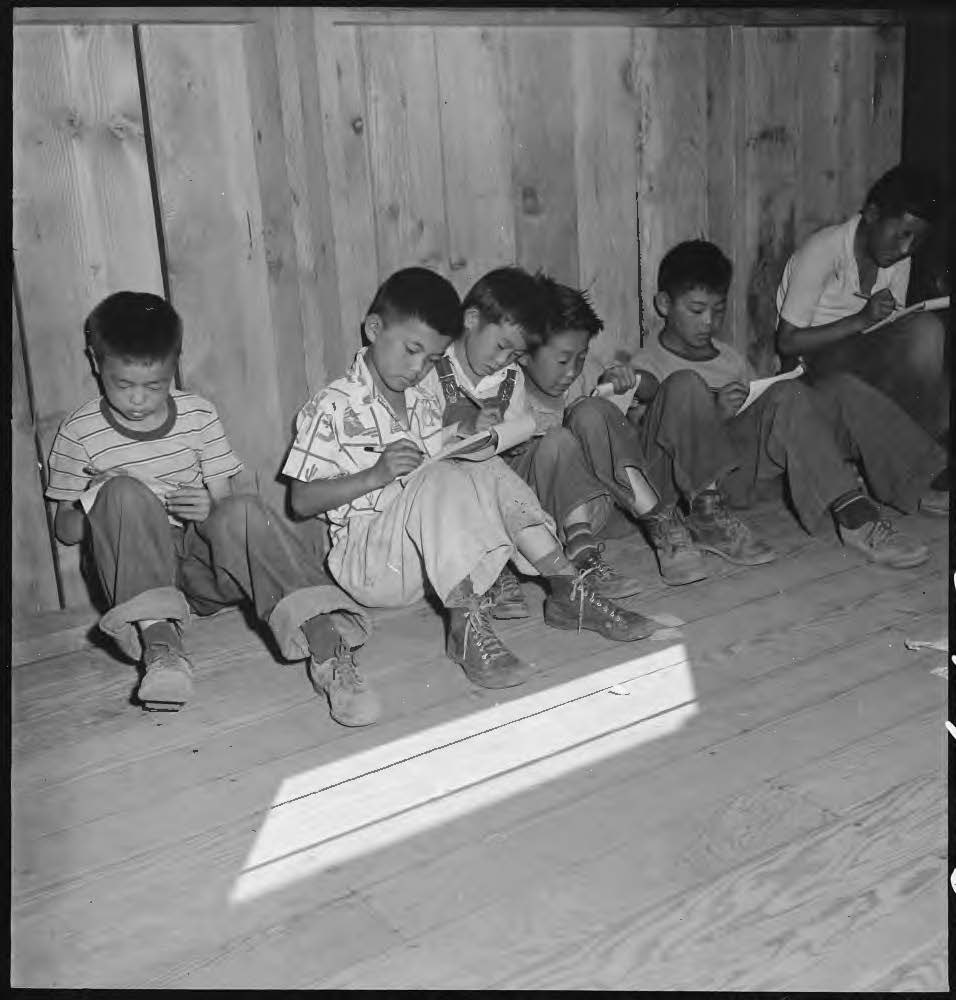

These camps, ten in total, were spread across seven states.viii The first to open was Manzanar, located in an isolated area in the southeast of California and operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Propaganda was carefully crafted to portray the camps positively, presenting the incarcerated people as content.ix Short films produced by the United States government including Japanese Relocation (1942) and A Challenge to Democracy (1944) gave an impression of dwellings that were well built, those forced into them as happy, and that the government was provided protection to their property as well as providing educational and employment opportunities. The WRA even organized curated tours for community leaders to visit the camps, showcasing only what they wanted the public to see.

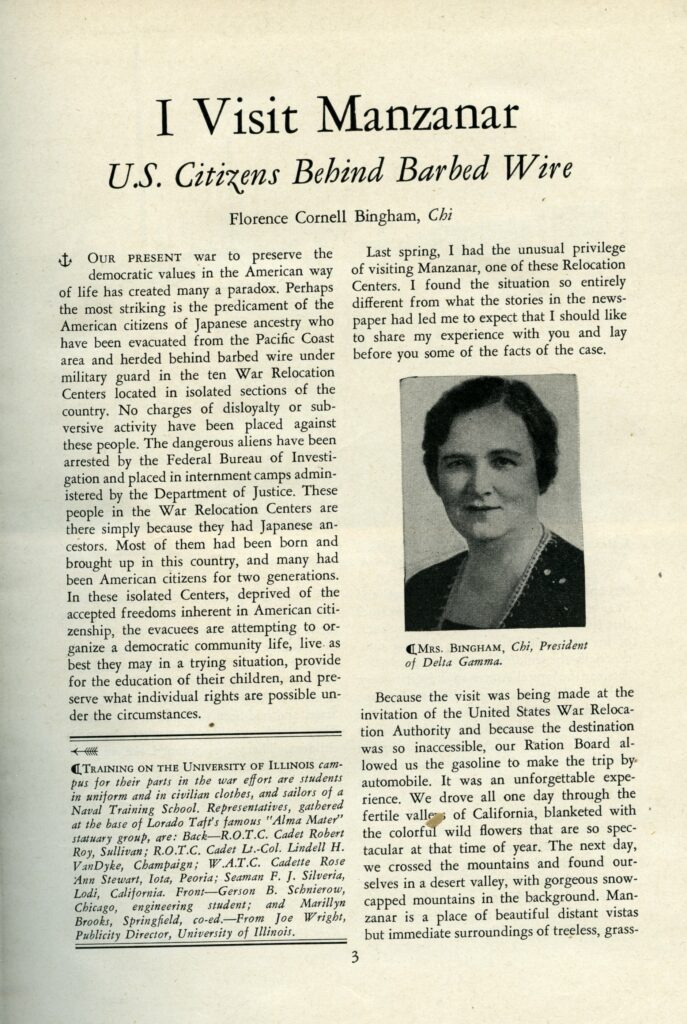

One such visitor was Florence Cornell Bingham, Upsilon–Stanford (initiated Chi-Cornell, later changed her affiliated chapter after relocating to California), who was involved with the California P.T.A. and Fraternity President of Delta Gamma. Invited by the WRA, Florence visited Manzanar twice, in 1943 and 1944. In her articles published in the ANCHORA, she highlighted the discrepancy between media portrayals and the harsh realities within the camps. Read the 1943 article here and the 1944 article here.

Florence vividly described the cramped living conditions, with six to eight people expected to share rooms of only 20 by 25 feet, lacking basic amenities like running water, toilets and cooking facilities. Communal bathrooms and cafeterias were the norm, and food was strictly rationed. Military police guarded the camp boundaries, and school rooms often lacked proper lighting, heating, ventilation and sanitation.

The weather was harsh, with temperatures soaring to 110°F and dropping below freezing. The high winds of the desert would coat the camp in layers of dust.x

While Florence's writings are not flawless, and her emphasis on "Americanization" may be viewed through a modern lens as downplaying Japanese identity, her dissenting opinions challenged the prevailing public sentiment. In 1942, the American Institute of Public Opinion found that 93% supported the incarceration of non-citizen Japanese Americans (issei), and 59% supported the incarceration of citizen Japanese Americans (nisei and sansei).xi

Delta Gamma's motto is "do good," and Florence embodied this by speaking out against injustice. She saw past the propaganda and expressed her dissenting opinion to Delta Gammas nationwide. Investigating the past allows us to learn valuable lessons for a better future. What lessons can we draw from this historical injustice? Share your thoughts and continue the conversation.

Terminology

You may have heard the term "internment camp" to describe places like Manzanar and the other camps. However, this is an inaccurate label. The National Park Service (NPS) provides a list of accurate terminology, revealing that the correct label for these sites is "concentration camps."xii In 1998, the Japanese American National Museum and the American Jewish Committee issued a joint statement addressing the use of the term "concentration camp" in this context.xiii

When discussing the movement of Japanese Americans into the assembly centers and ultimately the concentration camps, use terms liked “forced removal,” “expulsion,” and “mass removal” rather than “evacuation”. Furthermore, the term "incarceration" should be used instead of "imprisonment." Replace "imprisoned" or "prisoner" with "incarcerees" or "incarcerated person." Explore the NSP list of terminology and other provided sources for a more in-depth understanding.

iihttps://densho.org/learn/introduction/american-concentration-camps/

iiihttps://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/japanese-american-relocation

ivhttps://immigrationhistory.org/item/takao-ozawa-v-united-states-1922/

viiihttps://www.pbs.org/childofcamp/history/camps.html

ixhttps://immigrationhistory.org/item/takao-ozawa-v-united-states-1922/

xihttps://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust/main/japanese-american-internment